Fiscal Devaluation

19 Apr 2012During the boom years the competitiveness of the Irish economy deteriorated. Recovery depends on the restoration of our competitive position.

When an economy becomes uncompetitive, a standard way of addressing the problem is to devalue the currency. Ireland did this in 1986 and 1993. But as members of a currency union this option is no longer available

- A currency devaluation works by making exports cheaper and more competitive.

- Imports become more expensive leading to relatively higher demand for domestic goods and services.

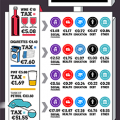

- This could involve increasing VAT and using the revenue raised to cut payroll taxes.

- An increase in VAT raises the price of imported goods. Since exports are exempt from VAT, the price of domestic exports will fall.

Changes in the mix of taxes can improve competitiveness without changing the exchange rate. (See “Fiscal Devaluation and Fiscal Consolidation: The VAT in Troubled Times“, Ruud de Mooij and Michael Keen, NBER Working Paper No 17913, March 2012).

Germany effectively carried out a fiscal devaluation in 2007 when it raised VAT from 16% to 19% and cut employers’ contribution to social insurance from 6.5% to 4.2%.

- Workers don’t bargain successfully for higher nominal wages because of the higher VAT rates. (if wages rise, this will offset the decline in tax costs)

- Firms use lower tax rates to cut export prices rather than maintaining the same export price and gaining a bigger profit margin from the lower tax rates.

The same conditions apply to a successful devaluation of the exchange rate.This policy can also help on the fiscal front. As is true of an exchange-rate devaluation, the positive impact on growth of an increase in competitiveness can strengthen the fiscal position by raising tax revenues.

What Does This Imply For Current Irish Tax Policy?

There is limited scope for a fiscal devaluation in Ireland today as there is little scope to cut any existing taxes. The tax burden will have to rise in order to reduce the deficit to below 3% by 2015 as we are committed to do under the EU/IMF Memorandum of Understanding.

This regressive effect could be offset by a change in the relative mix of taxes leading to an increase in employment. It could be argued that unemployment is extremely

regressive and that our economic policy should be subordinated to maximising the creation and retention of jobs.

This regressive effect could be offset by a change in the relative mix of taxes leading to an increase in employment. It could be argued that unemployment is extremely regressive and that our economic policy should be subordinated to maximising the creation and retention of jobs.